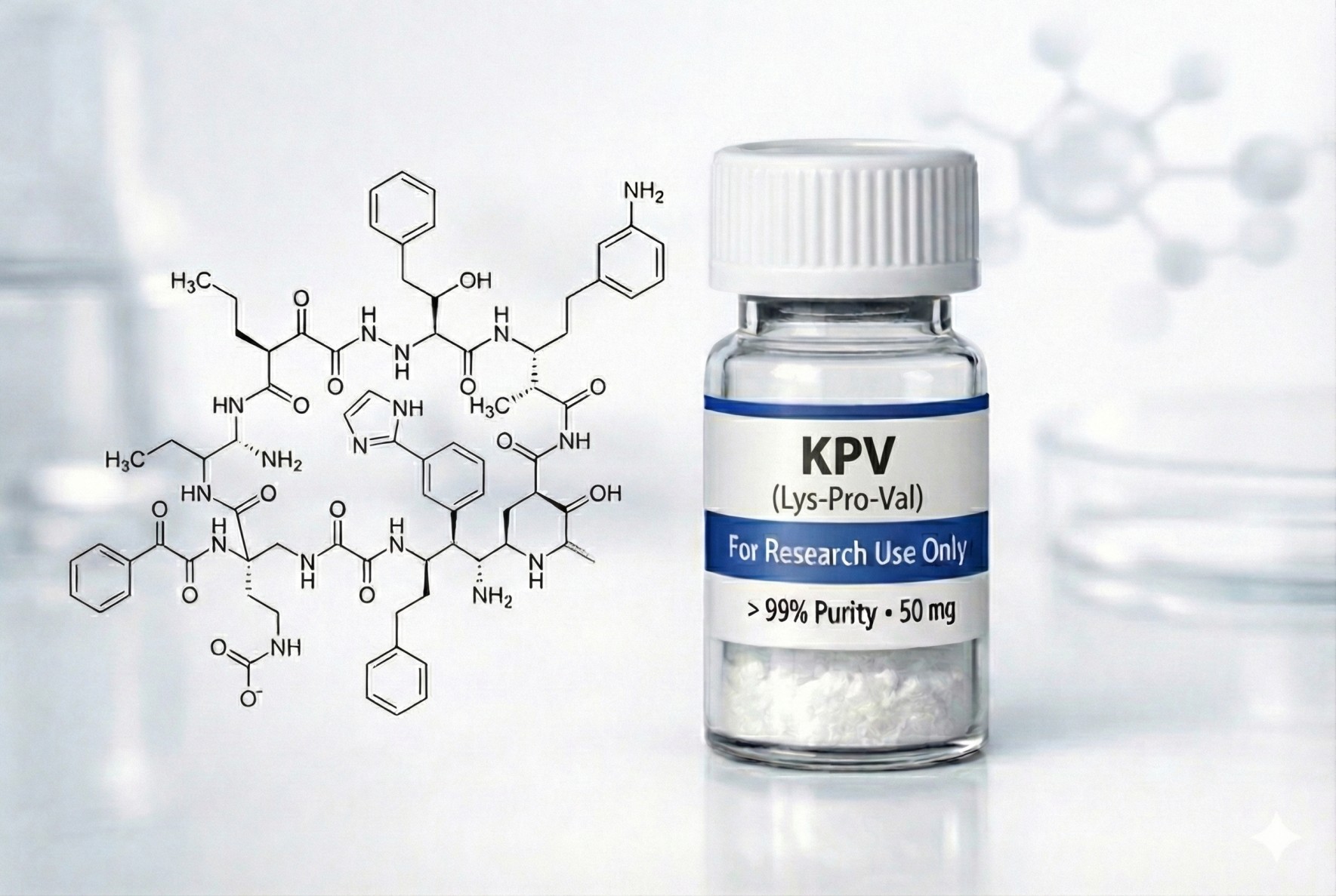

Description

KPV is a naturally occurring tripeptide with the amino acid sequence Lysine-Proline-Valine (Lys-Pro-Val) and molecular weight of 369 Da. The peptide represents the three C-terminal amino acids of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), a 13-amino acid neuropeptide hormone (Ac-Ser-Tyr-Ser-Met-Glu-His-Phe-Arg-Trp-Gly-Lys-Pro-Val-NH₂) that exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects when administered systemically or locally. α-MSH is derived from the precursor proopiomelanocortin (POMC) through post-translational proteolytic processing.

Historical Context:

α-MSH has been recognized since the late 1980s as having potent anti-inflammatory properties extending beyond its classical role in melanogenesis (skin pigmentation). Research by Luger, Lipton, and colleagues demonstrated that α-MSH could suppress inflammation in diverse experimental models including contact dermatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, asthma, and uveitis. However, clinical development of α-MSH as an anti-inflammatory agent faced limitations due to its melanotropic effects—binding to melanocortin receptors (particularly MC-1R) on melanocytes causes increased melanin production and skin darkening, an undesirable cosmetic side effect for chronic systemic use.

Research by Hiltz and Lipton in 1989 first demonstrated that the C-terminal tripeptide fragment KPV retained anti-inflammatory activity comparable to or even exceeding full-length α-MSH. Subsequent studies confirmed that KPV possesses “a similar or even more pronounced anti-inflammatory activity as full-length α-MSH” while eliminating melanotropic effects. This discovery opened the possibility of developing KPV as a targeted anti-inflammatory agent without cosmetic complications.

Unique Mechanism—PepT1 Transporter, Not Melanocortin Receptors:

Unlike α-MSH, which mediates anti-inflammatory effects primarily through melanocortin receptor (MC-1R, MC-3R) activation and cyclic AMP elevation, KPV operates via an entirely distinct mechanism:

Does Not Bind Melanocortin Receptors: Multiple studies confirmed that KPV does not bind to MC-1R, MC-3R, or MC-5R, does not increase intracellular cyclic AMP levels, and does not stimulate melanocytes. This explains why KPV lacks pigmentary effects despite retaining anti-inflammatory properties.

PepT1-Mediated Cellular Uptake: The landmark 2008 study by Dalmasso et al. at Emory University definitively established that KPV’s anti-inflammatory mechanism depends on cellular uptake via the PepT1 transporter (SLC15A1), an H⁺-coupled oligopeptide transporter that normally transports dietary di- and tripeptides in the small intestine.

Strategic Expression Pattern: PepT1 is normally expressed on the apical (luminal) membrane of small intestinal enterocytes but is virtually absent from normal colon. Critically, PepT1 is dramatically upregulated in inflamed colonic epithelial cells during inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), providing a disease-specific delivery mechanism. Additionally, immune cells including macrophages and T lymphocytes (Jurkat cells) express functional PepT1, allowing KPV to target both epithelial and immune components of intestinal inflammation.

High Affinity Transport: PepT1 transports KPV with remarkably high affinity (Km ~160 μM in Caco2-BBE intestinal epithelial cells, Km ~700 μM in Jurkat T cells)—among the lowest Km values reported for PepT1 substrates. For comparison, the commonly used PepT1 substrate Gly-Sar has Km ≥1 mM. This high affinity allows efficient cellular uptake at low nanomolar concentrations.

Intracellular Anti-Inflammatory Action: Once transported into cells, KPV accumulates intracellularly and directly inhibits inflammatory signaling cascades including NF-κB and MAPK pathways, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production (IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α).³ The peptide does not act at the cell surface but must enter cells to exert effects.

Pharmacological Characteristics:

Very Short Systemic Half-Life: As a small unmodified tripeptide, KPV is rapidly degraded by peptidases in serum and tissues, resulting in extremely short systemic half-life (likely minutes). This necessitates either frequent dosing, local administration, or advanced delivery systems.

Oral Bioavailability via PepT1: Unlike most peptides that are rapidly degraded in the gastrointestinal tract, KPV can be absorbed orally via PepT1 expressed on small intestinal enterocytes. Preclinical studies successfully demonstrated efficacy using oral administration (added to drinking water), with KPV reaching and acting on inflamed colonic tissues.

Local Action at Inflamed Sites: KPV’s dependence on PepT1—upregulated specifically in inflamed tissues—provides inherent targeting to sites of active inflammation while sparing normal tissues. This tissue-selective mechanism theoretically minimizes systemic side effects.

Nanoparticle Delivery Enhancement: Advanced drug delivery systems using hyaluronic acid-functionalized nanoparticles encapsulated in pH-sensitive hydrogels achieved 12,000-fold enhancement in anti-inflammatory potency compared to free KPV solution, allowing therapeutic effects at nanomolar concentrations.

Routes of Administration: Preclinical studies employed oral (drinking water), intraperitoneal injection, topical (cream/ointment), and advanced nanoparticle formulations.

Regulatory and Legal Status:

FDA Category 2 Classification (September 2023):

The FDA placed KPV on the Category 2 Bulk Drug Substances List, designating it as a substance that “raises significant safety concerns.” The agency specifically cited “lack of sufficient safety data for human use” among the grounds for this classification. This Category 2 designation effectively prohibits compounding pharmacies from using KPV in compounded medications under FDA regulations.

Zero Human Clinical Trials:

“There have been no human trials on KPV to date.” Despite over 15 years of preclinical research, KPV has never been evaluated in human subjects for safety or efficacy in any condition.

Never FDA-Approved:

KPV is not an FDA-approved drug and is not approved in any country surveyed. It has never undergone the regulatory process required for pharmaceutical approval.

Current Legal Status:

KPV is not a DEA scheduled substance, so possession is not illegal. However, the FDA Category 2 designation prohibits its use in compounded medications. The peptide remains legally sold as “research chemicals” or “dietary supplements”—classifications not subject to FDA regulations for pharmaceutical quality, safety, and efficacy. This creates a gray-area legal status where cash-based medical clinics offer KPV treatment despite zero human safety data and explicit FDA safety concerns.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.